Impact of Discontinuing Semaglutide After a Year

Recently, researchers from the Cleveland Clinic published a paper titled “Early- and later-stage persistence with antiobesity medications: A retrospective cohort study” in the journal Obesity.

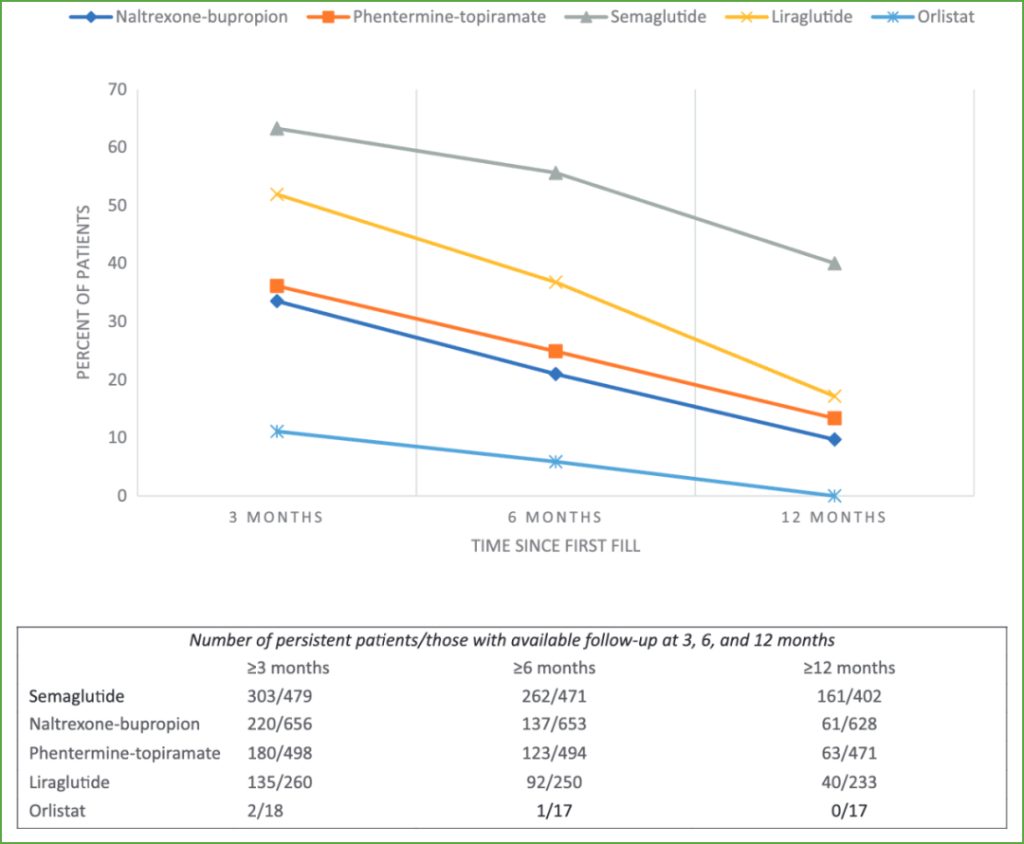

The study showed that among obese patients who were prescribed weight loss drugs (semaglutide, liraglutide, phentermine-topiramate, naltrexone-bupropion, orlistat) by doctors, 44% were still using the drugs after three months, 33% were still using the drugs after six months, and only 19% were still using the drugs after one year.

Among them, the proportion of obese patients using semaglutide who were still taking the medication after three months, six months and one year was 63%, 56% and 40% respectively.

Taking these drugs, such as semaglutide, consistently makes people feel full faster and longer, leading to effective weight loss. So why don’t these obese patients stick with them?

In fact, this is not uncommon. Patient nonadherence is also a well-known phenomenon for other diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and hypertension. Studies have shown that after one year, almost half of patients who use blood pressure medication will stop taking it.

Willingness to adhere to medication may be influenced by disease symptoms (e.g., lack of symptoms); aspects of the healthcare system (e.g., ability to access care or cost of medication); and characteristics of the treatment itself (e.g., how often it needs to be taken or how well side effects are tolerated). In fact, the frequency of GLP-1 medication use is important for people with diabetes; for example, those who use a once-weekly GLP-1 (semaglutide) are more likely to adhere to medication than those who use it daily (liraglutide).

The potential side effects of GLP-1 drugs have also raised concerns. In clinical trials, the rate of patients withdrawing from GLP-1 drug treatment ranged from 15% to 25%. About half of those who discontinued the drug did so because of side effects, mainly gastrointestinal problems.

But overall, side effects of GLP-1 drugs tend to be mild or moderate. Some people experience bouts of nausea within the first four weeks of using the drug, but this can get worse if the dose is increased. Diarrhea, constipation, fatigue and burping can also occur.

But it is worth noting that obese patients have much greater persistence using GLP-1 drugs than other weight loss drugs.

Clinical trials have shown that maximum weight loss with GLP-1 drugs takes about a year to achieve, and that about 6% weight loss can be achieved in 12 weeks, which would motivate people to stick with treatment.

In addition, the popularity of GLP-1 drugs has led to a global supply shortage, which may also cause some patients to stop taking the drugs because they can no longer obtain them.

While there is some controversy regarding the sustainability of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, the more relevant question is what happens when people stop this treatment.

These drugs may be hailed as “game changers” in helping people lose weight. But several clinical trials have shown that when the drugs are stopped, the weight lost can rebound significantly. For example, one clinical trial showed that participants treated with once-weekly semaglutide regained more than half of the weight they had lost within a year after stopping the drug. And a more recent clinical trial showed that those using telopoietin, a dual-target GLP-1 drug, also regained more than half of the weight they had lost after stopping the drug.

These studies concluded that weight loss can be maintained as long as the medication is not stopped.

We have long known that, regardless of the weight loss method used, people typically regain the weight once the intervention stops. Weight loss causes some biological and energetic changes that may make you healthier, but may also drive you to regain the weight you lost.

However, the way these new weight loss drugs work may mean that rebound is more likely. This is because the artificial GLP-1 injected is different from the GLP-1 your body produces (endogenous GLP-1).

Normally, GLP-1 is released after a meal, but it does not last long and is broken down quickly.

In contrast, the artificial GLP-1 injected is at a higher dose and lasts longer, equivalent to 10 times the normal active GLP-1, and such levels only occur naturally after eating a large meal.

The good news is that this not only makes you feel full, but also maintains that feeling of fullness, despite your body’s attempts to make you hungrier. However, maintaining such high levels of “fake” GLP-1 may cause your own endogenous GLP-1 to decrease.

So if you continue taking the medication and keep your GLP-1 levels artificially high, none of this is a problem. But if you suddenly stop taking the medication, your active GLP-1 levels will drop dramatically, so your body will no longer be restrained, and hunger and cravings may return with a vengeance. Combined with other factors, this can cause you to regain the weight you lost.

So we need to realize that these new generation of weight loss drugs, which are considered “game changers”, are making weight loss easier, but our focus should be on the main challenge of weight maintenance.